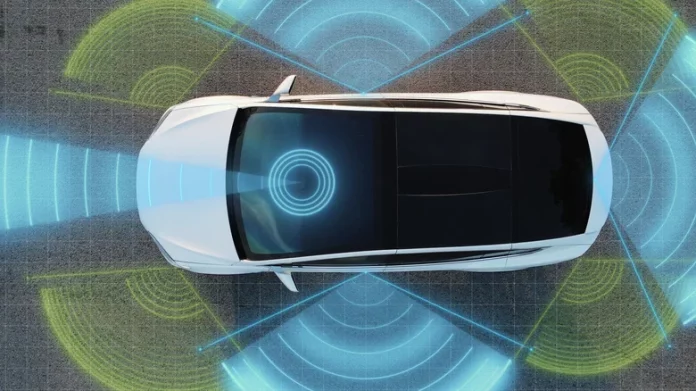

Modern vehicles, particularly those equipped with advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) or autonomous driving capabilities, increasingly rely on lidar sensors to navigate their environment. While this technology is a marvel of engineering, creating precise 3D maps by measuring reflected laser light, it introduces an unexpected risk to common personal electronics. The powerful, concentrated beams of infrared light emitted by these sensors, though invisible and generally safe for human eyes, can pose a serious threat to the delicate imaging sensors found in smartphone cameras. A direct exposure can permanently damage the camera’s photodiodes, resulting in burned or “fried” pixels that manifest as dead spots or lines in every photo and video. This hazard underscores a growing intersection between automotive innovation and everyday device safety, revealing that the sophisticated tools guiding our cars can inadvertently harm the tools we carry in our pockets.

Lidar’s Powerful Laser Light Can Fry a Camera Lens

Lidar, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, operates by emitting rapid pulses of laser light and calculating the time it takes for each pulse to reflect back to the sensor. This data is used to build a real-time, high-definition three-dimensional map of the vehicle’s surroundings, crucial for functions like adaptive cruise control, emergency braking, and semi-autonomous navigation. The lasers used are typically in the near-infrared spectrum, meaning they are invisible to the naked human eye. However, the silicon-based imaging sensors in digital cameras and smartphones are sensitive to a broad range of light wavelengths, including this infrared band. When a camera lens is pointed directly at an active lidar emitter, the sensor concentrates the intense laser energy onto a tiny area of its grid of photodiodes. This concentrated energy can overload and permanently damage those individual pixels, creating a condition known as sensor burnout. The damage is immediate and irreversible, as the microscopic components are physically altered. A widely circulated video demonstration showed this effect in real time, where a user zooming in on a Volvo EX90’s lidar sensor with a smartphone camera witnessed a trail of damaged pixels appearing instantly on the screen. In response to such incidents, automakers like Volvo have issued clear warnings, advising against pointing any camera directly at a vehicle’s lidar sensor to avoid potential damage.

Understanding the Risk and Practicing Caution

While the potential for damage is real, the everyday risk to the average person is relatively low and easily mitigated. The hazard primarily exists in a very specific scenario: when a camera lens is pointed directly at the lidar emitter from a close distance, especially if using optical or digital zoom, which further focuses the laser’s energy. Casual photography of a vehicle’s exterior, or even accidentally capturing the sensor in a wider shot, is unlikely to cause harm, as the laser’s energy is too dispersed. The greatest caution should be exercised by automotive enthusiasts, journalists, or technicians who might intentionally film or photograph sensor arrays up close. For these individuals, using a protective neutral density filter over the camera lens can significantly attenuate the intensity of the laser light. Furthermore, it is wise to power down the vehicle’s ADAS systems when performing detailed work on the sensors, if possible. For the general public, the key takeaway is awareness—simply understanding that the small, often discreet sensors on modern cars emit powerful, camera-damaging light. By avoiding the temptation to point a phone camera directly at these sensors for an inspection or video, users can protect their valuable devices while still appreciating the advanced technology that makes contemporary driving safer and more automated.