After Steve Jobs and Tim Cook, John Sculley is one of the most well-known figures to have led Apple. AppleInsider takes a close look at Sculley’s tenure at the company and the legacy history has assigned him.

When offered the role of CEO at a major company, one piece of advice is to negotiate your exit package before signing. John Sculley did precisely that. When he resigned from Apple on October 15, 1993, he walked away with what would be equivalent to $17.5 million in today’s money. This payout included severance, a year’s consulting fee, and Apple’s purchase of his mansion and private Lear jet.

Sculley is most famously remembered as the man who ousted Steve Jobs—or so the story goes. In 2009, CNBC ranked him as the 14th Worst American CEO of All Time, though even he didn’t top that dishonorable list (Lehman Brothers’ Dick Fuld claimed first place).

CEO payouts of this scale are hardly rare. No one begrudges Tim Cook his wealth for turning Apple into a $3 trillion company. But Sculley’s departure was not on the back of any comparable success. Rather, it was triggered by Apple’s grim quarterly results announced the day before his resignation.

Though Apple posted a profit and slightly increased sales, earnings plummeted 97 percent from the same quarter a year earlier. Apple’s net income shrank from $97.6 million to a mere $2.7 million, adjusted for 2025 dollars roughly $225 million down to about $6 million. Sculley’s earnings were sizeable; CNBC noted he was Silicon Valley’s highest-paid executive in 1987, pulling in around $2.2 million annually—about $6.3 million in today’s dollars. That was a tough pill to swallow amid Apple’s faltering fortunes, especially given his controversial reputation within the company.

Yet, a decade earlier, all seemed different.

Sculley Joins Apple

The iconic line Steve Jobs used to entice John Sculley to Apple is well-known: “Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world?”

At the time, Sculley was president of Pepsi, famous in the retail world for his role in the Pepsi Challenge campaign. Though he didn’t create the campaign itself, he commissioned research that revealed consumers preferred Pepsi over Coca-Cola in blind taste tests. Initially skeptical, Sculley later embraced the campaign and took it national, turning Pepsi Challenge into a hallmark marketing success.

Sculley candidly recalled an embarrassing moment when he publicly took the challenge and chose Coke, fortunately without media witnessing the slip.

Arrival at Apple

When Sculley came aboard Apple, replacing Mike Markkula as CEO, the media noted his background and marketing expertise. Markkula himself was a key figure in Apple’s early days, guiding the fledgling company for years.

Jobs initially wanted IBM’s Don Estridge as CEO, but when Estridge declined, he fixed on Sculley. Reports suggested Jobs preferred a CEO he could easily influence, though that strategy ultimately failed. After persistent persuasion over eighteen months, Sculley accepted the offer, which included a $1 million salary, signing bonus, stock options, and relocation expenses—a significant increase from his Pepsi pay.

The Apple Challenge

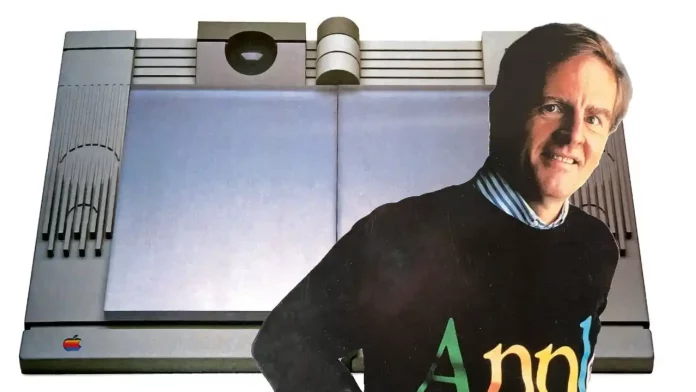

Despite criticisms, Sculley had notable successes. Steve Wozniak credited him with saving the Macintosh, which initially flopped but grew under Sculley’s stewardship once Jobs left. Wozniak also praised Sculley’s contributions to projects like the Newton, Knowledge Navigator, and HyperCard.

Sculley imported the Pepsi Challenge idea to Apple, launching the “Test Drive a Macintosh” campaign in 1984. For $2.5 million in advertising, consumers could try a Mac at home via a credit card security trial. While around 200,000 people participated, many returned the Macs, often damaged, undercutting the campaign’s success.

The 1985 Rift with Jobs

Initially friends, Jobs and Sculley’s relationship soured by 1985 amid Apple’s financial struggles. Sculley grew convinced Jobs was more trouble than asset. While he didn’t directly fire Jobs, boardroom clashes led to Jobs’ removal from company operations, prompting him to leave and start NeXT.

Sculley then led Apple alone for eight more years.

What Came Next

Sculley’s tenure is often seen through the lens of the Newton—a pioneering but flawed device that laid groundwork for smartphone innovation. While Sculley pushed the Newton concept, he later admitted hiring him was a “big mistake” due to his limited tech knowledge.

Under his leadership, Apple prematurely announced the Newton, giving competitors a head start. The product launched late and came with high costs and technical issues, ultimately hindering Apple’s market position.

Sculley was a capable corporate manager but failed to steer Apple in the innovative, timely direction it needed.

Lessons Learned

Shortly after leaving Apple, Sculley became CEO of Spectrum Information Technologies, a wireless tech startup. His tenure was rocky; he demoted founders, faced resignations, and left after four months amid legal disputes over undisclosed financial troubles.

Sculley himself admitted burnout and poor judgment, saying he ended up “with a bunch of bad characters.” Meanwhile, Steve Jobs returned to Apple, rescuing the company from financial ruin and reshaping it into the world’s most valuable brand.

Sculley’s Continued Vision

In 2025, Sculley retired from an AI marketing firm he founded, still offering insights on Apple’s future. Speaking at the Zeta Live Conference, he noted Apple’s upcoming leadership change and the need to embrace AI beyond apps.

He emphasized an era where autonomous “smart agents” automate workflows, a concept reminiscent of his 1987 Knowledge Navigator vision. While that concept hasn’t yet fully materialized, Apple’s advancements in AI suggest a step closer.

Perhaps it’s time for Sculley to let go of past dreams, but his mark on Apple’s history—a mix of vision, missteps, and bold marketing instincts—remains undeniable.